Weichsel glaciation 116 000-11 500 years ago

Weather has been changing dramatically for a long time. Cold wind sweeps over the glacier, not alone on the move; tiny creatures crawl amidst the icy mass. The bigger fauna dwell elsewhere.

Weather has been changing dramatically for a long time. Cold wind sweeps over the glacier, not alone on the move; tiny creatures crawl amidst the icy mass. The bigger fauna dwell elsewhere.

The Glacial age has prevailed for 2,5 million years, but once again the glacier starts to retreat. The Uusimaa region will however be covered with water for thousands of years to come. Finally a cold and barren land rise from the sea. Through times many species thrive on its riversides and shores, be they men, fauna or flora. They all meet the whole spectrum of life – some disappear, others prevail.

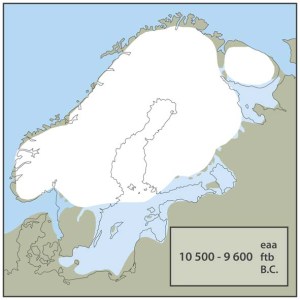

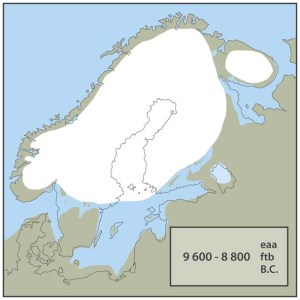

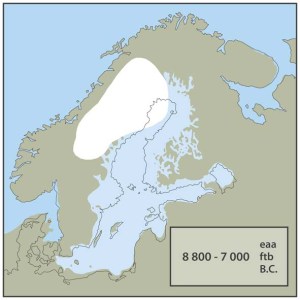

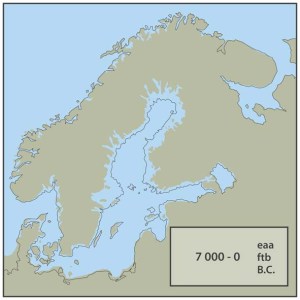

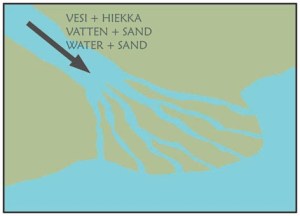

The Baltic Took Form

During the last 2 000 years the Baltic has not changed much.

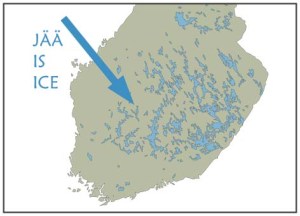

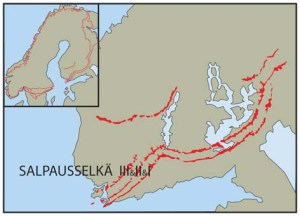

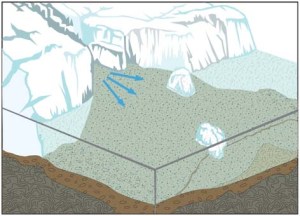

Shaped by the Ice

Several glacial periods affected the profile of the land and scraped off tens of meters of humus and sand. A barren and ancient bedrock or water surface was exposed 25-30 meters every year. When the burden was gone the ground, striving for balance, started to rise. And it is still rising.

7 000-6 500 years B.C.

The warmth of the blazing sun awakens the world. Seeds lie awaiting in the fragrant soil. Something wonderful is about to begin. Even the tiniest mole can feel the anxiety in the air. One has to beware the sharp nails and fangs, though. Dripping water melts the last patches of snow.

When the highest hills in the eastern Uusimaa region rise above the surface of the Litorina Sea, the climate is warm and relatively dry. For a long time plants and animals seem to hesitate whether to stay or leave. Former strangers find a place that suits many a different need.

Seasonal migrations between breeding and wintering grounds offer the best conditions for numerous animals. Rich food resources of the light northern summer attract many bird species to breed in the North but the milder climate in the South is more suitable for wintering.

Mesolithic Stone Age 8 600-5 000 years B.C.

The skier slides across the shimmering snow. The tracks lead to a small thicket. The dark mass of a Moose rises against the whiteness of the snow. The animal is skinny and small, but it will have to do. For a fleeting moment, all movement ceases. The stone point of the spear is well sharpened, the hunter’s hand steady. In one throw the dice of life and death is cast.

Humans follow on the tracks of animals and plants. Nature is setting the rules. One has to adapt to the seasons and the habits of the prey. The dog is an excellent hunting companion.

Let the Tool fit the Task

People knew their environment well and applied the diverse material offered by nature in an efficient and practical way. Also the prey was used to the last piece, from hide to horns and tendons. Since then, most of the organic material – wood, leather and bone – has disintegrated in the acid soil and only the parts made of stone remain.

Neolithic Stone Age 5 000-1 500 years B.C.

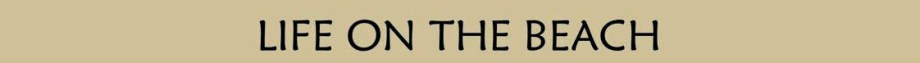

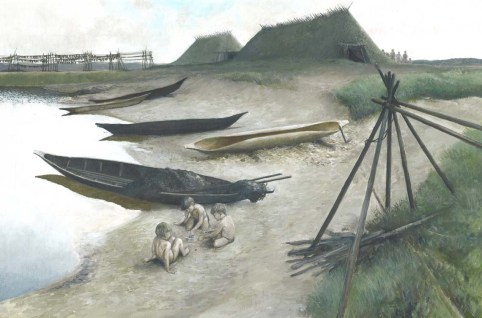

The sandy beach bathes in the sunshine. Children are playing down at the shoreline. Two slender boats glide to the shore. The long-awaited travelers are greeted by a cheering crowd. Do they bring gifts from faraway lands?

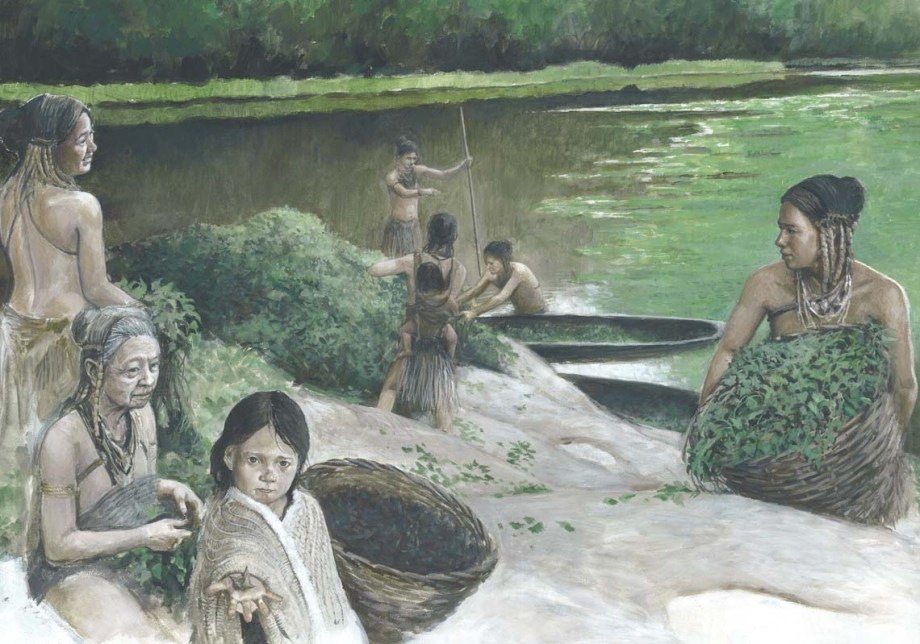

During the middle phase of Stone Age the climate is at its warmest ever since the Ice Age. The plants sensitive to cold grow far in the north. The south facing beaches are popular places to live and make camp. People master the art of pottery-making and are able to cover long distances.

During the Stone Age the oldest sites in eastern Uusimaa, Henttala and Munkkala, were inlets with excellent waterways. The sites are still inhabited.

The Water chestnut thrived in shallow and warm waters. It was an important source of protein. The nuts were eaten raw, heated or ground to flour.

Stone Age Treasures

Occasionally trade or other connections could obtain some rarities from far distances, even though the nearby nature was the most common source of raw material.

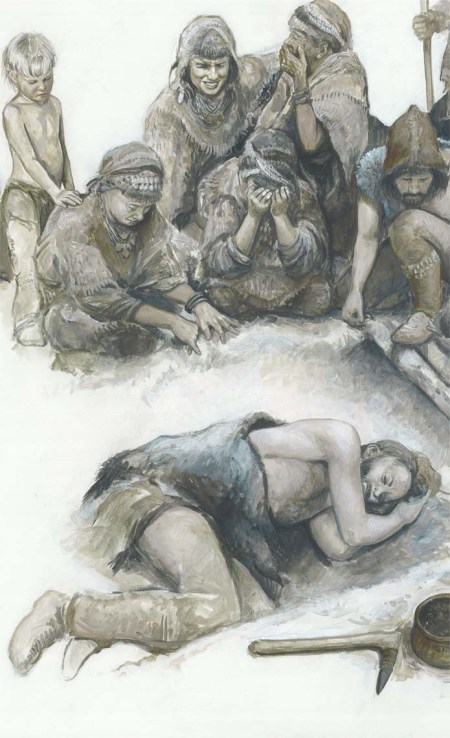

To the Bosom of the Earth

Relation towards death was probably an essential part of the people’s worldview. However, the lack of documents leaves the details in shadow. Many artefacts also accompanied the dead to the next life. During the early Stone Age bright red iron oxide had been strewn in graves, possibly symbolizing life and blood.

Bronze Age 1 500-500 years B.C.

A cold wind blows from the sea. There is still some grass left for the goats to graze on, but otherwise it is high time to stock for the coming winter. And someone has to repair the roof before the snow. If only one had enough furs to trade for a real axe of bronze!

Small-scaled cultivation and raising livestock have been practised since the late Stone Age although hunting and fishing have still remained the most important livelihoods. People begin to settle down. First bronze objects arrive to the north, but only the wealthiest can get hold of the imported metal.

Walls of buildings were constructed of poles and woven strips of wood, then sealed with a mixture of clay, animal dung and straw. (Model of a wall construction)

The Brilliant Bronze

Bronze is an alloy of copper and tin or some other metal. Bronze objects are cast in a mould.

Barrows as Graves

During the Bronze Age the ash of a deceased could be covered with a huge stack of stones, placed on a high cliff. The custom was probably applied only for the important members of the society.

Old McDonald had a farm

For ages the dog had been an excellent companion. Bringing also other animals to the farm is tempting as long as they are good natured, healthy and caring mothers.

During the late Stone Age swine, sheep and cattle were introduced. (reconstructions of youngsters of early domestic races)

SHEEP

During the Bronze Age the first shears appeared in Finland as the sheep no longer moulted in spring (like Mouflon). The course brown wool now had to be shared off. Later gray and white sheep were bred.

In the 1600th century sheep with finer wool were introduced. Imported thin textiles were to be replaced with native products. The local Nordic sheep were turning rare.

SWINE

The first domestic swine brought to the North are called ”forest swine”. This type of swine stayed the most common in the sty until the 1800th century. They were hairy with a long mug, small ears, long legs and varying colouration. Domestic swine are bred from Wild boar.

CATTLE

Cattle were primarily used as draught animals. As milk producers they were not significant until far later. By breeding the size of the animals reduced from the two meters high Aurochs to the height of the medieval cow of 110 centimetres.

Iron Age 500 years B.C.- year 1150

Again and again, the hammer strikes the glowing blade. Oh, if one day some chieftain should come and ask for a fine sword to be forged! But axes and knives, that is what the common people need. Few are those who have left these shores and headed to faraway lands, even fewer those, who have returned.

The skill of working iron has reached the north. Mastering the laborious process requires the special skills of a smith. People begin to form tribes and communities, often led by a chieftain. Traders and warriors travel south bringing back luxury goods and tales of wonder.

The climate was still cooling. Lakes started to fill up with weeds and the marshlands spread. Deciduous trees gave way to coniferous forests.

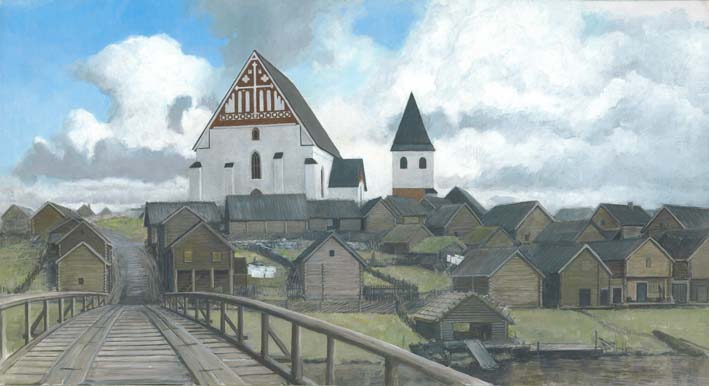

Middle Ages 1150-1570

Outposts of the Crown

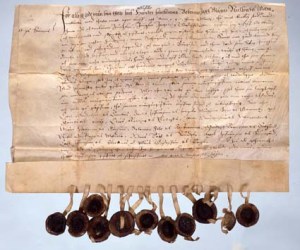

In the early Middle Ages both the Swedish crown and the eastern lords of Novgorod tried to claim dominance over the coastal region. During the troubled times high strongholds offered excellent vantage points place of refuge.

The hillforts of Linnamäki, Husholmen and Sibbesborg were likely to have been fortified by the order of the Swedish king in the late 14th century. Their main function was to demonstrate the might of the king and serve as headquarters for tax collection.

Eventually the wooden fortresses were deemed dispensable by the Danish Queen Margaret and demolished.

Late Middle Ages 1400-1599

The cart sways under the weight of the stones. The lads seem to be already waiting to hoist them up to the masons. The vaults should be finished before the snow, they say. Grand shall the new church surely be, but it is the common folk who do the paying with all the tithes and taxes. But every man has his share on this sorry Earth, and the Heavenly Grace awaits those, who do the Lord’s bidding.

From the 13th century onward Swedish speaking settlers start to inhabit the region. Porvoo is granted a town charter around year 1380. Trade is flourishing both with the inland and the town of Tallinn on the other side of the gulf. In 1550 the King orders the people to settle in newly founded Helsinki. Devastating fires make further damage to the town.

Mats Simonsson on a break

Mats the merchant’s hand enjoys the meal of a commoner in the time of fasting. The home-made rye bread is rather hard and the apple already quite wizened. At least the fish is fresh. Some sour milk mixed water to wash it all down, and there we go again.

Mats is wearing clothes made of wool and linen and dyed with plants. All the clothes have been made by Mats’ young wife. The merchant has given him leather shoes and the belt is made from and extra piece Mats got from a friendly cobbler.

In the Hands of the Almighty

Christianity arrived in the North with traders and clergymen. At first the doctrine and symbols were only beliefs and talismans among many. During the Middle Ages the Catholic Christianity settled as the only official religion.

Converting ”pagans” was not easy. Old gods and nature spirits long had their place beside the White Christ.

The church dominated the society. Great amounts of land were owned by the church, cloisters were centres of learning and archbishops rivaled kings in power and prestige.

Artisans

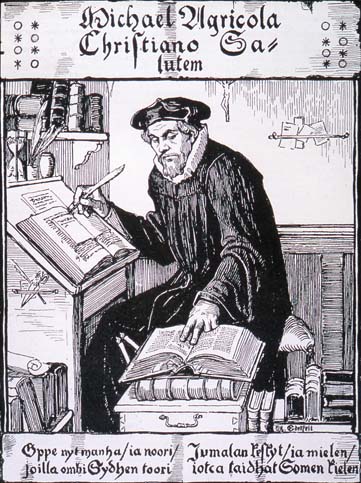

Mikael Agricola – From Pernaja to the Wide World

Mikael was born 1510 to a farming family in Pernaja. He had the privilege to be sent to school in Viipuri in order to become a clergyman. At the age of 26 Mikael signed up to the university of Wittenberg, where he began to use a latin surname Agricola, ”The Farmer”.

In Wittenberg Agricola adopted the Lutheran doctrine and after returning to Finland, began to translate religious texts to the language of the people, which was one of Lutheranism main theses. Finnish language was yet to have its literary form, and so Agricola’s alphabet was published five years prior to his translation of the New Testament in 1548.

Agricola was at the height of his career when king Gustav Vasa appointed him as the bishop of Turku. He died before reaching 50, when returning from a peace negotiations in Russia.

17th century

It is still dark behind the window, the room freezing cold. But one must leave the cosy warmth of the covers and be quick with the washing and brushing. Down the stairs, quietly as a mouse. A yawn cannot be stifled while kindling the embers in the master bedroom fireplace. Mistress’ garments are ready, and high time, there is already rustle behind the bed curtains. One cannot but hope that she has slept well…

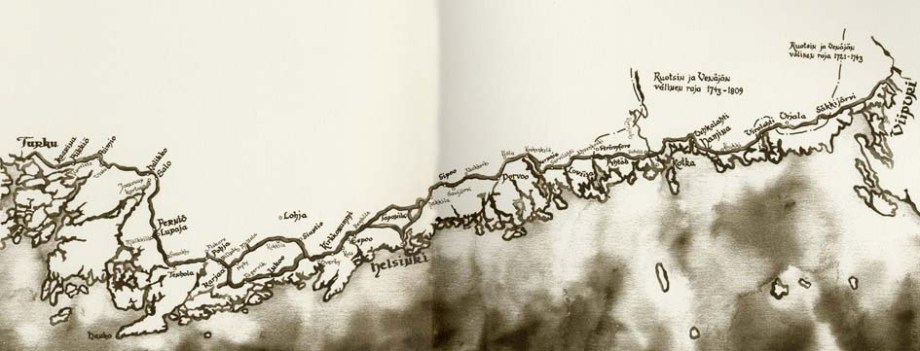

In the 17th century the Swedish Empire is at its height, but it requires waging war all around the Baltic. The Lutheran Church has established its power, and its tight decrees control the lives of each estate. The climate is cool and moist. Trade promotes building manors and manufactures.

Early 18th century

Sunset, time for the change of guard… Legs are almost numb already. Must not slip, though; someone has to guard all the supplies gathered from the good townsfolk. They had not much, poor souls, and were not exactly willing to contribute. Almost had a scuffle back there. But the soldiers of the crown got to have their share; otherwise it will be the Russians all over again.

Years of famine hold Finland in their grasp in the end of the 17th century. Desperate peasants are forced to abandon their homes, followed by pestilence and disease. Soon the unstable political situation between Sweden and Russia erupts into flames. The Great Northern War and the following Russian occupation, the Greater Wrath, mark the end of the Swedish Empire and the beginnings of a harsh and perilous era.

Town as a Garrison

Both Carolean and Russian soldiers were a common sight in Porvoo in the beginning of the 18th century. Their maintenance was a heavy burden for the townspeople. On the other hand, the soldiers brought some liveliness into the otherwise rather limited society.

Through the centuries, ruling the riversides has been both a chance and a challenge. Hopes and dreams have either met the surrounding realities, or succumbed to them. Either way, the legacy of the past lives on, in this day and all the days to come.

Contributors: Aktia Foundation, Svenska Kulturfonden

Object Loans: National Board of Antiquities

Special thanks to: Ilana Rimón, Tvärminne Zoological Station, Conservation Laboratory at the National Museum of Finland, Borgå Gymnasium, Congregation of Pyhtää, Olli Hakkarainen, Andreas and Riina Koivisto

Illustrations in colour: Tom Björklund